Ever wondered why some stories stick with you, reverberating long after the final page or credit roll, while others fade into a blurry recollection of "stuff happening"? The secret often lies in understanding Storylines & Plot Analysis. This isn't just about what happens in a narrative; it's about the deliberate architecture beneath the surface, the intricate dance of events designed to explore profound ideas, challenge assumptions, and evoke genuine emotion.

As a seasoned observer of narrative, I've spent years dissecting why stories work (or don't). What I've found is that truly engaging with a story means moving beyond passive consumption to active interrogation. It means seeing the plot not as a mere sequence of events, but as a carefully constructed argument or a provocative question posed to the audience.

At a Glance: Decoding Storylines & Plot Analysis

- Beyond Summary: Plot analysis unpacks ideas and themes implicitly conveyed through events, unlike a simple plot recap.

- The Skeleton: Plot is the fundamental structure of events, arranged to emphasize core concepts.

- Three Structures: Plots can be linear (chronological), circular (returning to the start), or in media res (starting in the middle).

- Conflict is King: Every story needs a problem or clash (Character vs. Character, Environment, or Self) to drive its narrative.

- Pivotal Moments: The Climax is the decisive turning point; the Dénouement is the aftermath, revealing full resolution.

- Narrative Journey: Stories often move from an initial balance (equilibrium) through disruption (disequilibrium) to a new state.

- Roles, Not Morals: Protagonist is the focus, Antagonist is the opposing force—neither is necessarily "good" or "evil."

- Active Engagement: Effective analysis requires a critical, questioning mindset to uncover deeper meanings.

Beyond the Surface: What Plot Analysis Truly Means

Many people conflate "plot" with "story." While intertwined, they're distinct. The story is the raw material – the chronological sequence of events. The plot is the artistic arrangement of those events, the choices made by the creator to reveal character, build suspense, or deliver a message. Think of it this way: a story is a list of ingredients; a plot is the recipe that brings them together, determining the flavor, texture, and presentation.

Plot analysis takes this understanding a step further. It's not about retelling what happened; that's plot summary. Instead, analysis delves into the why and how. How does the order of events develop specific ideas? What implicit messages are communicated through the narrative's structure? It's about looking at the literal occurrences—a chase scene, a quiet conversation, a difficult decision—and discerning the abstract concepts they illuminate about human nature, society, or the world itself.

For example, consider a simple story where a character loses a wallet. A summary would state, "The character lost their wallet and eventually found it." Plot analysis would ask: How did they lose it? Was it stolen (exploring themes of trust, vulnerability)? Was it misplaced due to distraction (exploring responsibility, consequence)? How did the search unfold? Did it reveal desperation, resourcefulness, or a surprising kindness from a stranger? Each choice in the plotting subtly shifts the underlying ideas.

The Architectural Blueprint: Understanding Plot Structures

Just as buildings have different architectural styles, plots can be structured in various ways, each serving a unique purpose in conveying meaning. The way events are arranged isn't arbitrary; it's a deliberate choice that shapes our perception and understanding of the narrative's core ideas.

The Linear Path: Chronological Storytelling

Most narratives you encounter follow a linear plot structure. Events unfold chronologically, one after another, from beginning to end. This is the most straightforward and often easiest to follow, allowing for a clear progression of cause and effect.

- Benefit: Provides clarity, builds anticipation incrementally, and often emphasizes character development over time.

- When it's used: Children's stories, many genre novels (fantasy, mystery, sci-fi), and historical accounts often rely on linear plots to guide the reader through a clear sequence of events.

- Example: A detective novel that begins with the crime, follows the investigation step-by-step, and concludes with the culprit's apprehension.

The Circular Journey: Returning to the Start

A circular plot structure begins and ends with the same event or situation, often incorporating a significant flashback or a journey that brings the protagonist back to their starting point, albeit transformed. The "return" isn't a reset; it emphasizes how much has changed internally, despite external circumstances seeming similar.

- Benefit: Highlights themes of change, growth, and the cyclical nature of life or experience. It often underscores irony or a hard-won lesson.

- When it's used: Fables, stories about self-discovery, or narratives exploring the futility of certain actions.

- Example: A protagonist leaves home to find adventure, faces many trials, and ultimately returns home, having gained wisdom but realizing what they truly valued was there all along.

In Media Res: Diving Into the Deep End

The Latin phrase "in media res" means "in the middle of things." This plot structure starts smack-dab in the middle of the action, often with a dramatic or pivotal event. The narrative then uses flashbacks or exposition to fill in the preceding events, while simultaneously moving forward.

- Benefit: Grabs attention immediately, creates intrigue, and allows for suspense by revealing information strategically over time. It can also suggest that the past is constantly influencing the present.

- When it's used: Epic poems (like Homer's The Odyssey), thrillers, and stories where the context of past events is crucial to understanding the present conflict.

- Example: A character awakens in an unfamiliar place with amnesia and must piece together their past while simultaneously escaping danger. The story immediately plunges you into their present predicament, only later revealing how they got there.

The choice of plot structure is a powerful tool for the storyteller. It fundamentally dictates how ideas are introduced, how tension is managed, and ultimately, how the narrative's central message is delivered.

The Engine of Story: Understanding Narrative Conflict

Without conflict, there is no story. Period. Narrative conflict is the problem, clash, or issue that drives the narrative arc forward. It's the friction that sparks interest, creates tension, and forces characters (and by extension, the audience) to engage with the stakes at hand. Epic or intimate, a story lives or dies by its conflict.

Think of conflict as the engine of a car. Without it, the vehicle is just a static collection of parts. The engine makes it move, overcome obstacles, and reach its destination. Similarly, conflict propels the plot, challenging characters and revealing their true nature.

There are three primary types of narrative conflict, though longer works often intertwine multiple forms:

1. Character vs. Character (External)

This is perhaps the most recognizable form of conflict, pitting one character directly against another. It's a clash of wills, ideologies, goals, or personalities.

- What it reveals: Power dynamics, moral ambiguities, the struggle for dominance, or the complexities of interpersonal relationships.

- Analysis questions: What do these characters represent? What's at stake beyond their immediate interaction? Are their motivations justified from their own perspectives?

- Micro-example: A hero battling a villain, a sibling rivalry for parental approval, a courtroom drama between opposing lawyers.

2. Character vs. Natural or Social Environment (External)

This conflict type involves a character struggling against external forces beyond individual control.

- Character vs. Natural Environment: The character faces off against the elements, a wild animal, or the unforgiving landscape itself.

- What it reveals: Human resilience, vulnerability to nature's power, themes of survival, or humanity's place in the natural world.

- Micro-example: A lone explorer battling a blizzard, a group trying to survive on a deserted island, a community dealing with a devastating earthquake.

- Character vs. Social Environment: The character is up against societal norms, oppressive institutions, cultural expectations, or widespread prejudice.

- What it reveals: Injustice, the struggle for identity or freedom, the impact of collective ideologies, or the courage required to defy the status quo.

- Micro-example: An individual fighting against a corrupt government, a person challenging deeply ingrained social prejudices, a young inventor struggling to gain acceptance for a radical new idea. In the world of The Speed Racer Next Generation cartoon, Speed's adventures often involve him and his friends challenging corrupt racing organizations or technologically advanced adversaries, showcasing a character vs. social/technological environment conflict as much as character vs. character.

3. Character vs. Self (Internal)

Often the most profound and universally relatable, this conflict involves a character grappling with their own internal struggles, moral dilemmas, conflicting desires, or psychological demons.

- What it reveals: The complexities of the human psyche, themes of identity, moral decision-making, self-acceptance, or the journey of personal growth.

- Analysis questions: What internal demons or virtues are being explored? How does this internal battle manifest externally? What is the character forced to confront about themselves?

- Micro-example: A character torn between duty and love, someone battling addiction, a person trying to overcome their own fears or self-doubt.

Analyzing the specific type and nature of the central conflict (and any sub-conflicts) is paramount. It tells you immediately what ideas the story is most interested in exploring and how it intends to challenge or reassure the audience.

The Narrative Arc: From Equilibrium to Resolution

Stories, at their most fundamental, describe a journey. This journey typically moves from a state of equilibrium (initial balance) to disequilibrium (disruption or problem), and then to a new state of equilibrium. This doesn't necessarily mean a "happy ending" in the traditional sense; it simply means the central conflict has been resolved, and a new, stable (though perhaps drastically altered) reality has been established.

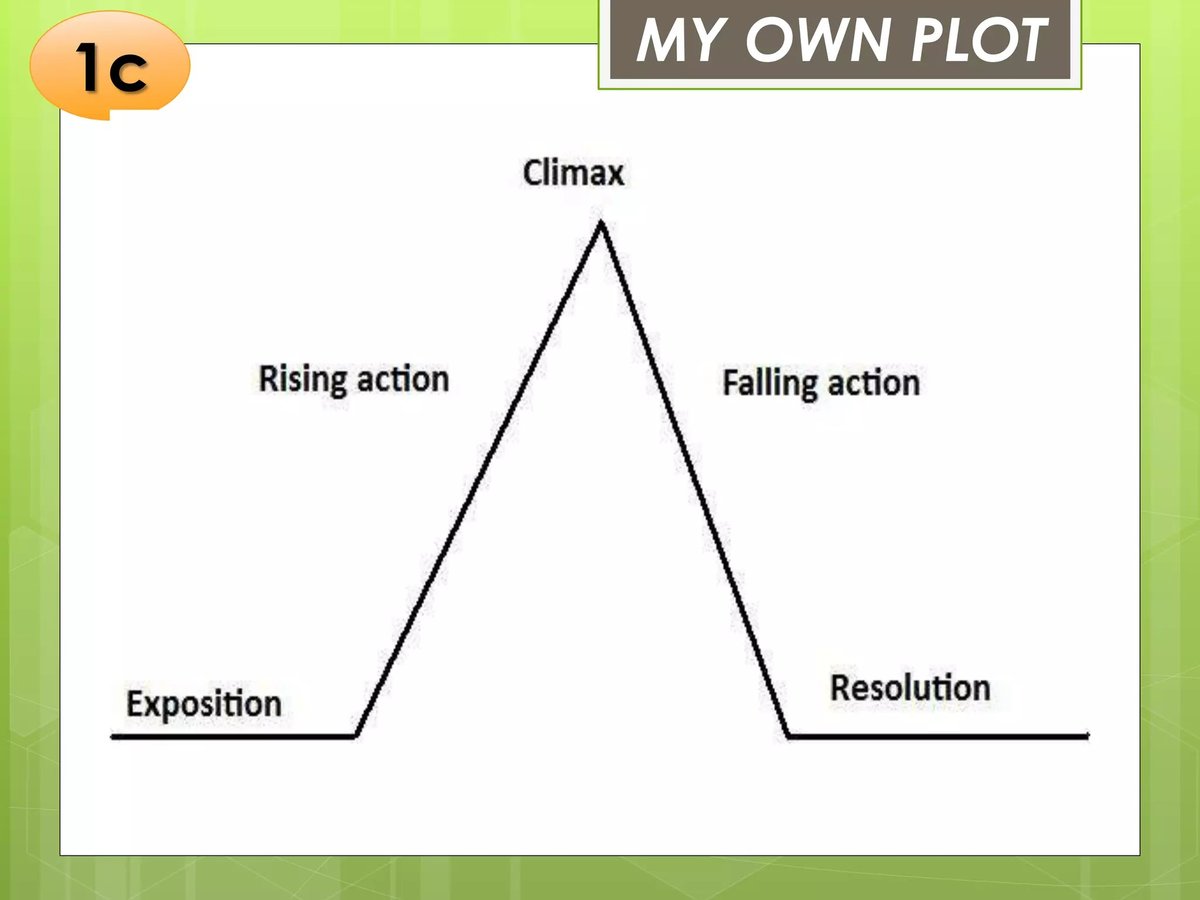

- Initial Equilibrium: This is the "normal" world of the story, before the main conflict begins. It establishes the characters, setting, and the status quo. It helps the audience understand what's at stake when that status quo is threatened.

- Inciting Incident: The event that shatters the initial equilibrium, introducing the central conflict and kicking off the main plot.

- Rising Action: The series of events, complications, and challenges that escalate the conflict, building tension and propelling the protagonist toward the story's turning point.

- Climax: This is the pivotal act, the decisive moment that determines the outcome of the central conflict. It's the peak of tension and the point of no return. It might not be the most dramatic moment in terms of spectacle, but it's where the protagonist makes a choice or faces a challenge that irreversibly alters their path.

- For analysis: The climax is crucial because it often explicitly reveals the story's "answer" to the central question posed by the conflict. What choice is made? What truth is revealed?

- Falling Action: The events immediately following the climax, where the consequences of the climax begin to unfold, and the story winds down.

- Dénouement (Resolution): French for "unknotting," the dénouement is the aftermath of the climax, where the repercussions and full resolution of the conflict play out. Loose ends are tied up, characters come to terms with the new reality, and the story settles into its new state of equilibrium.

- For analysis: The dénouement reveals the final implications of the narrative's journey. What is the new status quo? What lessons have been learned, or what truths confirmed or refuted? Does the "new equilibrium" offer hope, despair, or a complex mix?

Understanding this arc allows you to trace the story's thematic development. By mapping the changes from the initial to the final equilibrium, you can uncover the author's commentary on human experience.

The Players: Protagonists, Antagonists, and Their Nuances

Stories are driven by characters, and their roles within the plot are often defined by their relationship to the central conflict. However, it's vital to shed preconceived notions of "good guys" and "bad guys" when conducting plot analysis.

The Protagonist: Your Narrative Anchor

The protagonist is the main center of narrative focus. This is the character (or occasionally, group of characters) whose journey we follow, whose choices drive the plot, and through whose eyes we often experience the story.

- Key Distinction: The protagonist is not necessarily a "hero." They can be flawed, morally ambiguous, or even outright unlikeable. Their defining characteristic is their central role in the narrative and their engagement with the primary conflict.

- Analysis Tip: Instead of asking "Is this character good?", ask "What challenges do they face, and how do their responses reveal the story's ideas about courage, morality, ambition, or survival?"

The Antagonist: The Force of Opposition

The antagonist is the figure or force that causes problems for the protagonist, creating obstacles and driving the conflict.

- Key Distinction: The antagonist is not necessarily a "villain." The antagonistic force can be another character with opposing goals, a societal institution, a natural disaster, a set of personal circumstances, or even an internal struggle within the protagonist themselves.

- Analysis Tip: Focus on what the antagonist represents. If it's a character, what are their motivations? If it's a force, what ideas or systems does it embody? The antagonist often acts as a mirror, revealing facets of the protagonist or challenging the story's core values.

For example, in a survival story, the harsh wilderness might be the antagonist. In a coming-of-age tale, the protagonist's own shyness or self-doubt could be the antagonist. By identifying these roles clearly, you gain a sharper understanding of the forces at play and the nature of the story's central argument.

Mastering the Craft: How to Analyze Plot Effectively

To truly unlock a story's deeper meanings, you need to shift from passive consumption to active, critical engagement. This isn't about "ruining" a story; it's about enriching your experience by understanding its construction.

1. Adopt a Detached, Critical Approach

Resist the urge to simply enjoy the ride. Instead, cultivate a "detective's mindset." Step back emotionally and observe the narrative as if it were a complex mechanism.

- Ask "Why?": Don't just accept events; question their purpose. "Why did this happen now?" "Why was this detail included?"

- Look Beyond the Surface: Every event, every character interaction, every structural choice is a deliberate decision by the storyteller. Your job is to uncover that intention.

2. Identify the Central Narrative Conflict

This is your anchor. Every other element of the plot should somehow relate to this core problem.

- What is the fundamental clash? Is it a person against another, a person against society, or a person against their own nature?

- What ideas or issues does this conflict present? Does it highlight injustice, explore the nature of good and evil, or question societal norms? Pinpointing this helps you understand the story's thematic heart.

3. Map the Narrative Arc

Trace the story's journey from its initial state to its final resolution.

- What is the initial equilibrium? What is "normal" before the story truly begins?

- What is the inciting incident? What event disrupts that normal?

- How does the conflict escalate? Note the major turning points and complications.

- What is the climax? The definitive choice or moment of no return. What is decided here?

- What is the new state of equilibrium? How has the world, or the protagonist, changed? What are the lasting consequences?

4. Examine Character and Setting in Relation to Plot

Plot is never isolated. It's intricately connected with other fictional elements.

- Character: How do the protagonist's actions and decisions drive the plot? How do they react to the conflict? How do other characters' actions influence the trajectory of events?

- Setting: Does the setting itself act as an antagonistic force? Does it influence the types of conflicts that can arise? Does it reflect or highlight thematic ideas (e.g., a decaying city representing societal decline)?

5. Look for Patterns and Repetitions

Authors often use recurring motifs, imagery, or plot devices to emphasize ideas.

- Symbolism: Are certain objects, colors, or actions repeated? What might they represent?

- Parallelism: Do similar events or character reactions occur in different parts of the story? What contrast or comparison is being drawn?

6. Consider the Author's Choices

Ultimately, plot is a series of choices. Why did the author choose a linear plot over in media res? Why did they resolve the conflict in a particular way?

- What if it were different? Imagine alternative plot choices. How would that change the story's meaning or impact? This helps you appreciate the significance of the actual choices made.

Common Misconceptions & Pitfalls to Avoid

Even seasoned readers can fall into common traps when analyzing plot. Steering clear of these can dramatically improve the depth and accuracy of your insights.

Misconception 1: "Plot is just what happens."

Reality Check: While events are central, plot is fundamentally about how those events are arranged and why. It's the artistic choices that elevate a simple sequence into a meaningful narrative. Focus on the structure and its purpose.

Misconception 2: "The climax is always the most dramatic or action-packed scene."

Reality Check: Not necessarily. The climax is the decisive moment, the point where the central conflict's outcome is determined. This can be a quiet, internal realization or a difficult choice, rather than an explosive battle. A character simply making a crucial confession could be far more climactic than a high-speed chase if that confession resolves the core tension.

Misconception 3: "The protagonist must be heroic, and the antagonist must be evil."

Reality Check: These are roles, not moral judgments. A protagonist can be deeply flawed or even morally compromised, and an antagonist can have perfectly understandable (even sympathetic) motivations. Focusing on their function in driving the conflict, rather than labeling them "good" or "bad," leads to richer analysis.

Misconception 4: "Plot analysis is just criticizing the story."

Reality Check: Analysis is about understanding. It's a deeper form of appreciation. By dissecting how a story works, you gain respect for the author's craft and the complexity of their message. It's not about finding fault, but about uncovering artistry.

Pitfall: Getting Bogged Down in Summary

Remember, the goal is to move from the literal events to the abstract ideas they express. Don't spend too much time recounting what happened. Instead, quickly summarize an event, then immediately pivot to "This event illustrates...", "Through this choice, the story explores...", or "The arrangement of these scenes emphasizes...".

Pitfall: Imposing Your Own Ideas

While interpretation is key, ground your analysis in the text itself. Avoid projecting your personal beliefs or desires onto the narrative. Instead, ask: "What evidence from the plot supports this interpretation?" Stick to what the story implicitly (or explicitly) suggests through its events and their arrangement.

Your Next Chapter: Applying Plot Analysis

The beauty of understanding storylines and plot analysis is that it fundamentally changes how you engage with all narratives. Whether you're reading a novel, watching a film, binging a TV series, or even listening to a friend recount their day, you'll start to see the underlying structures, the driving conflicts, and the ideas being put in play.

This isn't just an academic exercise. For writers, it's a blueprint for crafting compelling stories that resonate. For readers, it's a superpower that deepens appreciation, sparks critical thought, and transforms entertainment into profound engagement.

So, the next time you encounter a story, don't just ask "What happens next?" Instead, lean in, observe, and ask: "How is this plot crafted to make me feel, think, and understand the world a little differently?" The answers you uncover will reveal not just the story's secrets, but perhaps a few of your own.